Photo: Michelle Young

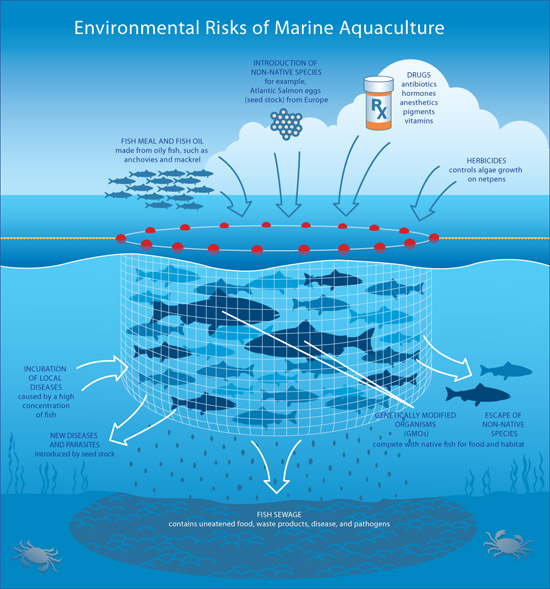

Open-net pen salmon farms pose serious threats to Pacific salmon and the marine environment.

In 2012, the Cohen Inquiry released its report on the 2009 collapse of Fraser River sockeye salmon and clearly indicated that open-net pen farms are problematic. Judge Cohen made many recommendations, but unfortunately, few have been implemented.

Aquaculture can be beneficial to society if it is practiced sustainably. Alternative technologies, like closed containment systems, are viable alternatives to troublesome open-net pen farms.

About the Cohen Commision

What are open-net pen fish farms?

Open-net pen fish farms rear fish in large cages that are suspended in the ocean. The only barrier between the farmed fish and the surrounding environment is a net, so water flows from the ocean through the farms. The farms can be located in offshore or coastal environments, though most are found in sheltered areas like bays.

Open-net pen fish farms were first introduced to the coast of British Columbia in the 1970s and significantly expanded in the 1980s. Over 100 open-net pen salmon farms exist along the province’s coast. Farms are located near and amongst the Discovery Islands, Broughton Archipelago, Tofino, Barkley Sound, Ocean Falls, Campbell River, Sayward, Port McNeill and along the Sunshine Coast.

Over 95% of the biomass produced by open-net pen fish farms in British Columbia consists of a non-native species, Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). Most of these Atlantic salmon originate from Norway, where they are reared in freshwater before being transferred to B.C.’s open-net pen farms as smolts.

Threats from open-net pen fish farms are harming wild salmon and damaging coastal ecosystems

Piscine orthoreovirus (PRV)

PRV is a virus known to cause disease in farmed Atlantic salmon. The virus can lead to a condition called heart and skeletal inflammation disease (HSMI). HSMI can cause high mortality rates in farmed Atlantic salmon and therefore economic losses in the salmon farming industry.

Studies show that PRV can be transferred from farmed Atlantic salmon to wild Pacific salmon. Dr. Brian Riddell, former president and CEO of the Pacific Salmon Foundation states “these findings add to the existing concerns about the potential impacts of open net salmon farming on wild Pacific salmon off the coast of B.C.”

There is significant concern that wild Pacific salmon migrating past disease-infested farms are at high risk of PRV infection. Wild Pacific salmon populations are declining, and the PRV-related risks open-net fish farms present to these vulnerable populations are unacceptable.

Sea lice

Sea lice are a naturally occurring marine parasite that can be found wherever salmonid fish species occur. The small crustaceans feed on the skin and mucous of fish. It is normal for adult salmon to carry a few sea lice. Sea lice become problematic when they attach to juvenile salmon; even a small number of lice can kill a young salmon.

Research shows that sea lice from open-net pen Atlantic salmon farms are infecting wild salmon populations. The farms hold 500,000 to 750,000 salmon in dense concentrations, creating an environment where sea lice are able to reproduce at an incredibly high rate. Since water flows through open-net pen farms to the surrounding area, high concentrations of sea lice are found in surrounding waters used by migrating wild Pacific salmon.

A massive sea lice infestation was reported in May 2018 in Clayoquot Sound where fish farm operator Cermaq reported that over half of its 14 farms were infested with sea lice levels that posed a serious threat to wild salmon. Fish farm companies try to reduce sea lice populations by releasing toxic chemicals into open-net pens, which then spread to the surrounding marine environment. By law, fish farm companies are required to keep sea lice levels at an average of three motile lice per adult fish. In the case of the Cermaq outbreak, sea lice levels averaged 34 lice per fish, over 10 times the acceptable limit.

Blood water

Once harvested, farmed Atlantic salmon are sent to processing plants where they are prepared for export. Processing plant waste – called blood water – is pumped into the ocean and disperses into the marine environment. Blood water poses a threat to other species because the waste contains bacteria and viruses found in farmed fish.

The issue of blood water first caught the public’s attention when Tavish Campbell, an avid diver and ecotourism employee on Vancouver Island, filmed blood water spewing into the ocean. Samples taken from blood water outflows have been tested by the Atlantic Veterinary College and results revealed the samples were infected with PRV.

Wild salmon are at risk because the treatment of processing plant effluent is not adequately regulated. In December 2018, the B.C. government made a commitment to strengthen fish farm regulations to ensure wild Pacific salmon are protected from threats posed by parasites and blood water.

Wild salmon are integral to B.C.

British Columbia depends on healthy populations of wild B.C. salmon. First Nations communities have relied on abundant salmon for millennia to sustain their communities. They are a key part of our economy and form the backbone of our province’s rich river ecosystems.

According to a report prepared for the Pacific Salmon Commission, B.C.’s wild salmon fisheries – both recreational and commercial – generate nearly $1 billion and 9450 full time equivalent jobs each year. Salmon are also vital to B.C.’s wildlife tourism industry, which employs over 26,000 people and contributes $1.5 billion to the economy annually. The most popular species to observe – whales, bears and birds – all depend on salmon for survival.

Wild Salmon are in trouble

Overall abundance of B.C.’s wild salmon has declined since the 1950s for a variety of reasons. The summer of 2017 saw some of the lowest returns of wild salmon on record across the entire province. The decline of wild salmon has had negative impacts on wildlife that depend on the availability of abundant salmon to survive.

On B.C.’s south coast 9 of 15 Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) populations are endangered. Chinook salmon account for 82% of the diet of endangered Southern Resident Killer Whales (SRKW), of which only 73 remain. The biggest threat faced by SRKW is prey availability and the population is currently experiencing severe malnutrition which is impairing their ability to reproduce. If Chinook salmon populations fail to recover, SRKW will be pushed even closer to extinction.

A viable and safe alternative: Land-based closed-containment recirculating aquaculture systems

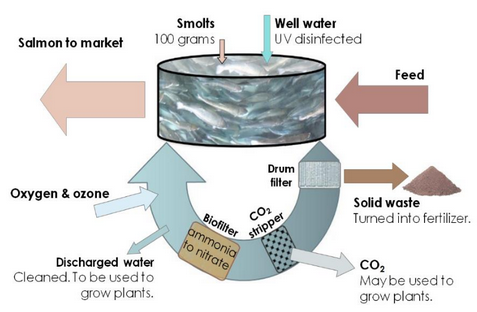

Land-based closed-containment recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS) completely separate fish farming operations from the marine environment. Containing farmed fish in land-based tanks eliminates the environmental and economic risks presented by open-net pen farms and removes all interactions between wild species and farmed fish. Advances in this technology now allow for 99% water recycling within the system, further reducing the environmental impact of farmed fish.

RAS eliminates farmed fish losses due to disease, sea lice infestation, algal blooms, predators, temperature variations, storms and escapes. The farming method also creates optimal rearing conditions, allowing for the control of all parameters throughout the grow-out process. As a result, farmed fish are healthy, grow quickly and live in antibiotic-free and low-stress conditions.

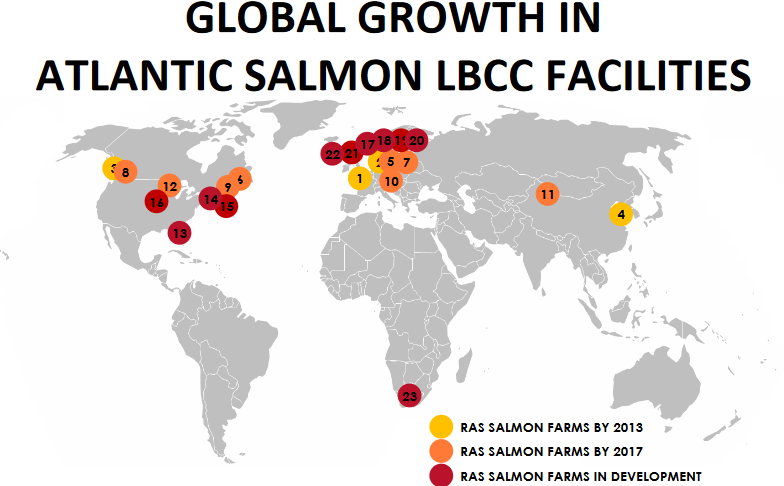

The fish farming industry is moving to land-based, closed containment systems around the globe. Though there is opportunity for RAS systems in B.C. and Canada, adoption of this sustainable fish farming method has been slow due to a lack of government support.

Global growth in land-based closed containment Atlantic salmon aquaculture (Source: Living Oceans Society)