Southern resident killer whales. Photo: Rachael Merrett

Southern resident orcas are one of the most highly studied whale populations in the world. Every individual has a name and is photographed for an annual census that has been conducted for over 40 years by the Centre for Whale Research. We know their family trees, when they were born, who they favour spending time with, and even their individual personality traits. What we don’t know is where they are.

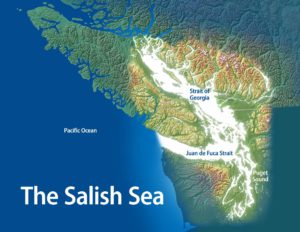

Research on the southern residents began in 1976 when the capture of wild killer whales for aquariums from the waters off the Pacific Northwest officially ended. Dr. Michael Bigg, a scientist for Fisheries and Oceans Canada, coined the term ‘residents’ to describe this family of whales as they were seen year after year in the inland waters of south Vancouver Island and Washington from spring until the end of fall, as they fed on the abundant runs of chinook salmon heading towards the Fraser River.

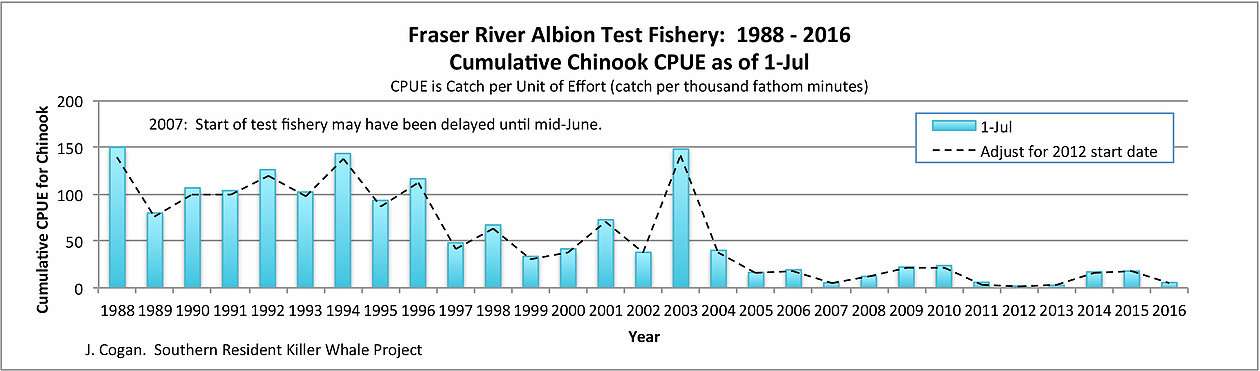

Since 2013 sightings of the resident killer whales within the Salish Sea have become scarce. Historically, years with low resident sightings correspond with low chinook salmon returns to the Fraser River. According to the Albion Test Fishery, 2013 was one of the two worst years on record for chinook salmon returns to the Fraser River (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Graph sourced from the Center for Whale Research. The graph demonstrates the cumulative catch per unit effort (CPUE) of Fraser River chinook salmon as of July 1 for each of the years beginning in 1988, with the dashed line representing an adjustment for the late start in the fishery opening using 2012 as the reference year for a late start. Click on image to enlarge.

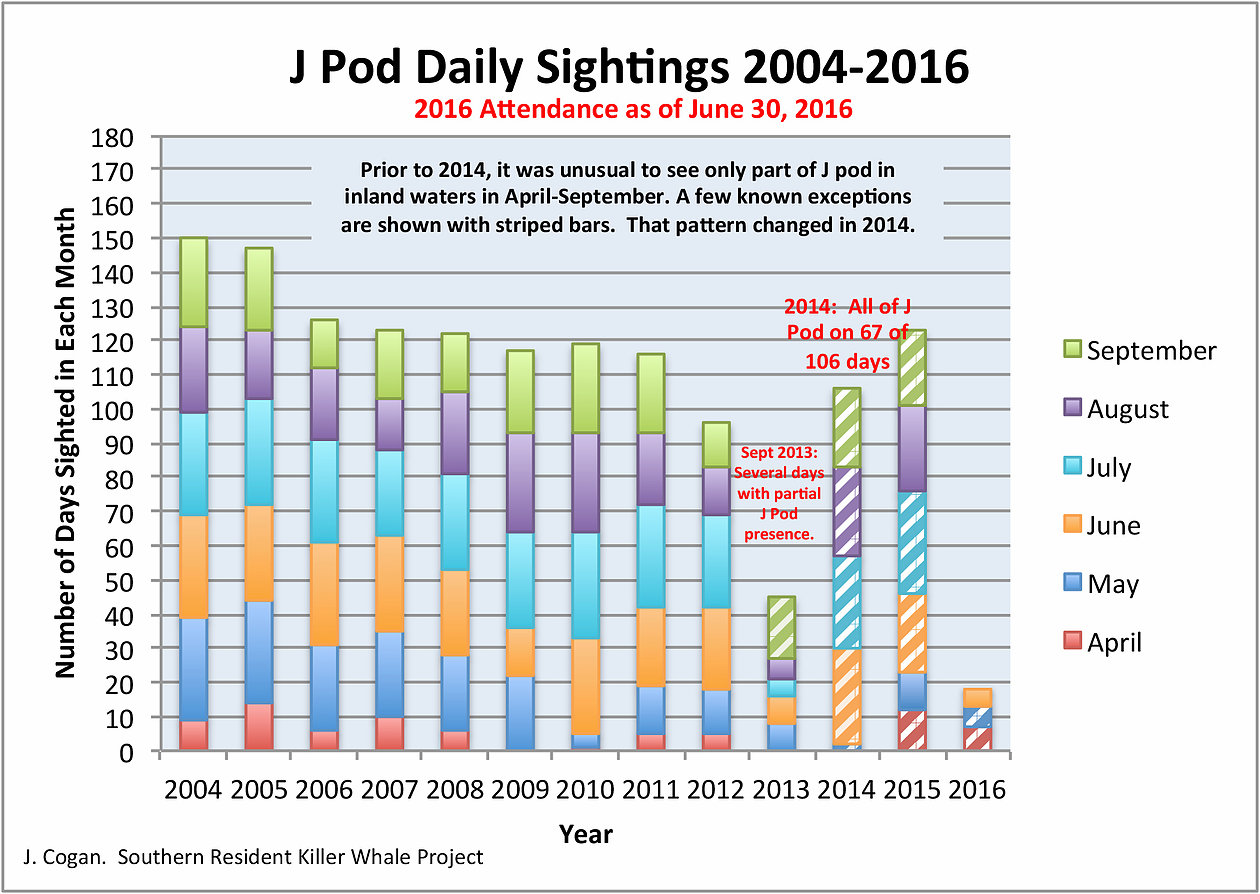

J-pod – one of 3 pods that make up the resident orca population – has historically been the pod that is seen most often in the Salish Sea during the summer. However, in 2013 they were only seen 45 times by the Center for Whale Research from April to the end of September, a period of time when they tend to feed on chinook salmon heading to the Fraser River. Compare this to 2004 when chinook salmon returns were higher: J-pod was seen 150 times in that time span.

Figure 2: Graph sourced from the Center for Whale Research. The graph depicts the number of sightings of J-pod from 2004 to 2016 in their core summer habitat from April through September. Sightings for 2016 only cover April, May and June. Solid coloured bars illustrate sightings of the entire pod while striped bars represent sightings with only parts of the pods present. Click on image to enlarge.

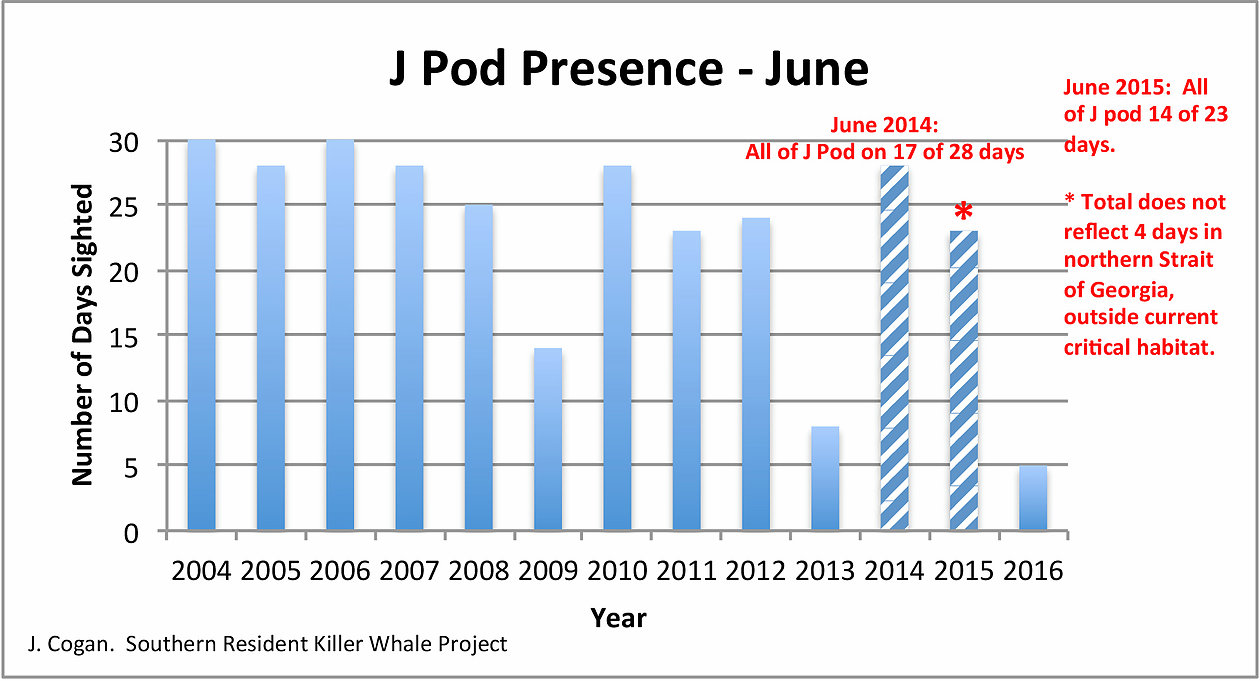

Another record low year for Fraser River chinook returns occurred in 2016 and that year southern residents were only seen five times in the month of June. This season, once again, we are seeing record low returns of chinook salmon and the southern residents were only reported in the area once in the month of June. This illustrates a stark contrast when compared to previous years where J-pod was seen 20-30 times in the same month.

Not only are the whales not returning to the Salish Sea as much as they historically have, the pods are now fragmenting into smaller groups. Prior to 2013, this had never been recorded by the Centre for Whale Research. When a pod came in, everyone who belonged to that family was present. But in 2013, they started to see the pods break up into smaller groups. Experts are hypothesizing that there is no longer enough food to feed the entire pod, so the families have to separate in order to find the nutrition they need to survive. The question remains as to whether the families are finding enough food somewhere else. From their visibly poor body conditions, that seems unlikely.

Killer whales are very social animals who maintain strong family bonds. They thrive on physical contact and vocalize to each other almost constantly.

Figure 3: Graph sourced from the Center for Whale Research. The graph depicts the number of times J-pod was seen in their core summer habitat in the month of June from 2004 to 2016. Click on image to enlarge.

Centre for Whale Research staff are reporting that they are concerned that the breakup of the pods could pose a health risk to the population that likely cannot be measured. They note that long term starvation in humans can cause a variety of emotional disorders, including withdrawal from social activity, decreased sex drive and apathy. These conditions are also often seen in humans when there is a breakdown in community. It is fair to say that similar conditions could occur in orca populations. Not only are the whales starving, their families are fracturing, compounding the emotional and mental health threats that can be onset by both starvation and social structure breakdown.

Not only are the whales starving, their families are fracturing, compounding the emotional and mental health threats that can be onset by both starvation and social structure breakdown.

How Does 2017 look?

Not good.

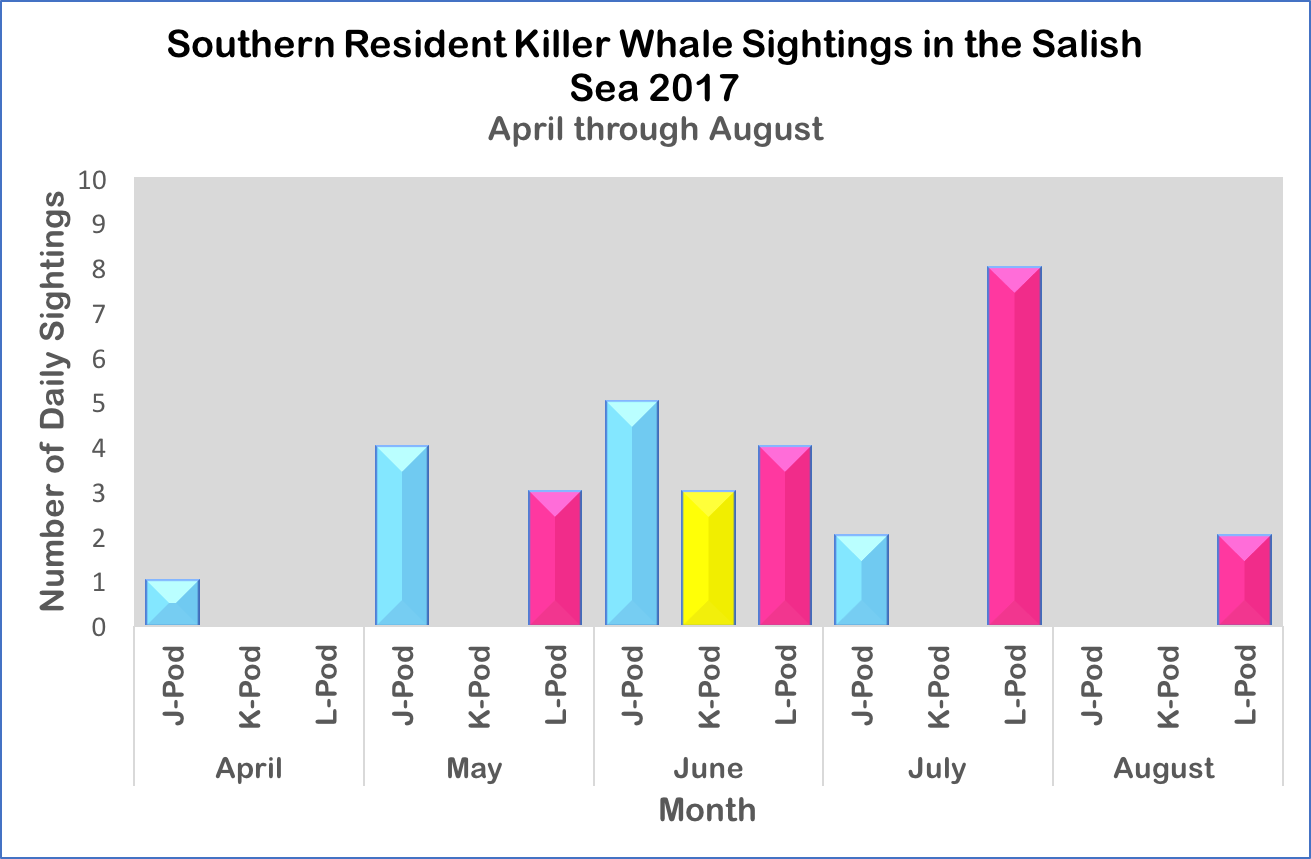

Sightings records were collected from the Centre for Whale Research, Orca Network and from Victoria whale watching reports. Combined, there have been just 27 sightings of the southern residents in the Salish Sea from April 1st to August 31st. Interesting to note is that most of these sightings were of L-pod, or in most cases just part of L-pod, contrasting to historical trends of J-pod being seen most often in the area. Another important observation has been that only the K-14 matriline has been seen in local waters this summer.

Figure 4: Data collected from sightings reports from Centre for Whale Research, Orca Network and Victoria whale watching reports. A majority of the sightings reports only documented partial pod presence. Created by Rachael Merrett, GSA. Click on image to enlarge.

If the whales are not here, where are they?

We have contacted the Marine Education and Research Society and Stubb’s Island Whale Watching to see if the southern residents have been spotted in northern areas of British Columbia. They have not had any sightings of the southern residents in Johnstone Strait or Queen Charlotte Strait in 2017. We have not been able to find any other reported sightings of the southern residents from anywhere else along the BC coastline. Are they in offshore areas of the Pacific Northwest? Could they be looking for food in Alaska? Nobody at this point has the answers to these questions.

What does this mean?

Photo: Rachael Merrett

Without sightings of the families, it is impossible to track their health and any births or deaths that may have occurred. This is critical information that needs to be gathered so that we know what is happening within the population. For example, we do know that J-22 or Oreo was very pregnant in May of this year. Researchers are anxious to know if her pregnancy was carried to term, and if so, what is the condition of mother and calf.

Another concern is regarding fragmentation of the pods and the complete lack of superpod events where all three pods are present in the same area at the same time. This may lead to a breakdown in community cohesion and overall population familiarity. Southern residents used to regularly gather together in superpods where they would be seen mating, socializing, and foraging with members of all three pods. This no longer happens.

Will the fragmentation of the pods and lack of time spent together affect reproduction? Will the potential breakdown in social structure influence their health and/or mortality rates?

Researchers will not be able to collect and analyze any data on the southern residents if we don’t know where they are.

Another concern is whether or not their absence from the Salish Sea will be permanent as this will affect protection and recovery efforts being implemented by both Canadian and U.S. governments, researchers and NGO’s. If the whales no longer use the Salish Sea as their core summer habitat, where are they spending their summers? If somewhere else, recovery measures will need to be adjusted. The status of chinook salmon populations who spawn in the Fraser River appear to be playing a key role in determining whether the southern residents will continue to be absent from the Salish Sea in the future. If Fraser River chinook stocks are protected and allowed to recover, we will likely see the return of the southern residents to the local waters that we know they have used consistently for decades, especially if we are also reducing the other threats to this population

What can we do?

Photo: Rachael Merrett

We are working to push the government to take meaningful action to protect the resident orcas and we’ll need your help at key times to increase that pressure. Stay informed about new developments pertaining to the southern resident killer whales by joining the Orca Action Team – we’ll keep you updated and let you know when you need to take action. You can also help the whales by donating to our Orcas Can’t Wait Fund– your donations will be matched until the end of summer to double the impact, and help us be there to help the orcas.

You can read more about the threats to the southern residents in our blogs:

No Salmon = No Orca »

Drowning in Noise »

Toxic Waters – Toxic Food »

It would seem that the pods have not been radio tagged and so now it is a big puzzle as to where they went. More attention also needs to be paid to sightseeing businesses and others coming too close to get pictures as evident from some of the videos we see.

It’s long been a mystery as to where they go – tagging is a sometimes controversial way to monitor them so may be why that hasn’t been done. Drones are helping with monitoring and giving us more information. We have been waiting many years for the federal government to approve new Marine Mammal Regulations which will give more enforcement teeth to deal with harassment of whales. We are pressuring the govt to make this part of their new Ocean Protection Plan

It is way beyond the time to stop the herring roe fishery in the Salish Sea. Pre – 1970s there were small populations of herring throughout the Gulf of Georgia and through continued mismanagement they have all but gone. The spawning herring arriving from off the west coast of Vancouver Island have increased (temporarily during spawning) the biomass and this is used to justify the wasteful herring roe fishery. This is the last herring roe fishery on the BC Coast. These herring are the part of the food web feeding salmon , dolphins and whales and innumerable smaller species. It must be stopped if the Salish Sea is to survive.

We need stronger restrictions of fishing of many stocks, including herring and Chinook salmon. It’s clear the govt isn’t quite ready to take the needed action to protect the food wildlife, including orcas, need. We have to continue to pressure them to act now.

It breaks my heart to hear this bad news about the Chinook Salmon and Orca’s….I wish I could help financially but I just can’t…

I am sending these articles to my family in Alberta who I’m sure have no idea why we here on the coast are so against the oil companies building more pipelines and the transportation of the product to the Orient…Maybe if I send them this info they will understand why these magnificent animals need a more quiet ocean ,at least not worse than it is now ,in order for them to communicate with each other and how important it is to not ruin their habitat and feeding grounds anymore than they are now…

With much love to the Orca’s

Sharon Karp

Thank you for sharing this information with your family – it’s so important that all Canadians understand what’s at risk and why we fight everyday to protect our coast.