On the west coast, wild Pacific salmon lie at the heart of our cultural identity.

Five species of Pacific salmon (Chinook, coho, pink, sockeye and chum) hatch from eggs in our freshwater rivers, streams and lakes, then spend the bulk of their lives in the sea.

Five species of Pacific salmon (Chinook, coho, pink, sockeye and chum) hatch from eggs in our freshwater rivers, streams and lakes, then spend the bulk of their lives in the sea.

At the end of their life cycle, they return to the rivers to spawn another generation, and then they die.

Wild salmon face incredible obstacles in order to return to spawn in the exact spot in which they were born – often far up a river into BC’s interior.

Salmon Feed the Land and Water

For millennia, returning wild salmon have been feeding humans, seals, whales, eagles, wolves, bears and even fertilize our forests.

Because they are bringing nutrients from the Pacific Ocean in their bodies, wild Pacific salmon even feed the forests, as their carcasses are spread around the forest by bears, wolves, birds, and other animals. This replenishes the soil and nourishes the trees, which would otherwise have run out of nutrients a long time ago.

Because they are bringing nutrients from the Pacific Ocean in their bodies, wild Pacific salmon even feed the forests, as their carcasses are spread around the forest by bears, wolves, birds, and other animals. This replenishes the soil and nourishes the trees, which would otherwise have run out of nutrients a long time ago.

Wild salmon are a reminder of how much we don’t know about the ocean. It was only recently, using nitrogen isotope analysis, that scientists learned about the dependency of forests, hundreds of miles from the coast, on fish that live most of their lives in the ocean.

They’re also a vivid reminder of the link between the ocean and the continent, the salt water and the fresh – and the knowledge that what we do on the land directly affects the health of the ocean.

The Threats to Salmon

In British Columbia we have already lost more than 140 unique salmon runs. About 600 more runs are in peril. This is the result of poor fisheries management over many years and degradation of critical habitat. We have allowed our rivers and streams to be dammed, drained, warmed and filled with sediment and debris.

Pollution has also contributed to their decline. Whether you’re a coastal resident or not, we all live “upstream”. Eventually, everything finds its way to the ocean. The tons of sewage we produce don’t just go away when we flush. The toxic household products that go down our drains, pesticides and fertilizers that wash off our lawns and playing fields, fossil fuel emissions from our cars, agricultural chemicals, industrial pollutants, logging debris and sediments – all of these end up in the ocean, moving up the marine food chain.

Now that climate change is causing summer temperatures to rise in our rivers, streams and estuaries, wild salmon are in more peril than ever.

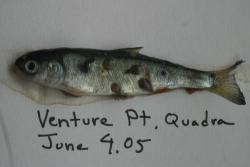

Jody Eriksson and Miray Campbell sampling juvenile salmon for sea lice at Venture Point. Photo by Ruby Berry

The Cohen Inquiry

We saw a dramatic example of what lies ahead if we don’t take meaningful steps to reduce threats to our salmon in 2009 with the collapse of the Fraser River salmon run. The result was the Cohen Inquiry and acknowledgement by scientists of the urgency of this situation. The 75 recommendations have been mostly ignored though a 2016 government re-commitment to them gives us some hope.

Fish farms and hatcheries are not the answer – they cannot replace the essential roles wild salmon play in coastal ecosystems.

Wild salmon are a supremely renewable resource. We need to restore their habitat and encourage them to return forever – for our own sake as well as theirs.